This November, our award-winning production of Idris Goodwin’s HYPE MAN is back for 3 NIGHTS ONLY as a special fall fundraising event in support of C1’s New Play Development.

Author Archives: Lauren Miller

Poolside Politics: A Conversation with Ruby Rae Spiegel

Playwright Ruby Rae Spiegel and Dramaturg Jessie Baxter recently took some time to chat about the driving force behind Dry Land’s inception and why it’s important to tell teen stories.

JESSIE: What was your inspiration for writing this play?

RUBY: It was a couple things — there was this article that I read called “The Rise of the DIY Abortion” in the New Republic, and that really got the ball rolling in my head. When I work, I usually pair a piece of journalism with my own experience, and I had also helped a friend through, not an abortion, but something similar and quite difficult. That was a very profound experience for me, so that plus the article got me thinking about women’s bodies and friendship, and how those intersect in these times of crisis. Buy Generic Cialis http://www.healthfirstpharmacy.net/cialis.html

Did you swim as a teen?

Yeah, I was a swimmer on a team in middle school, but I actually wasn’t very athletic. I quit right when flip-turns became a thing, because I was just too scared. I wasn’t a very good swimmer, but I was a very good pianist. I played piano for 11 years of my life, until I was 15, and I worked really hard at that. So I kind of paired those two experiences together. With piano, I internally pushed myself a lot and worked really hard from a young age, and I think that’s something that young athletes have a lot experience with.

Swimming is also an interesting choice for the play because even though it’s a team sport, it’s still a very solitary activity.

R: Absolutely, swimming has this divide where you might be working together on a relay race or something, but it’s really your body alone in the pool. I remember hearing the gun go off, and you just go into your zone. My other interest in talking about swimming and athletes was that we hear a lot about girls being tough on their bodies because of media images, and I was interested in exploring that and eating disorders, but from a different angle — where someone is really pushing their body and obsessed with perfection, but in a way that doesn’t have to do with beauty standards.

I’m interested in your choice to focus on the teen girl experience. How did you approach these characters?

The dialogue just sort of flowed for me, I think because I’m so close to those ages. In high school I wrote a play about middle school, and in college I wrote a play about high school…I like to write when I have a bit of perspective, but maybe not too much perspective, that I start to narrativize an experience. Something that I get frustrated with is that you see a lot portrayals of teenagers where there’s a really simple way that they draw it back to the parenting. If a teen has an issue, it’s because they have this certain kind of home or something, and that has always felt like it doesn’t give teenagers enough credit. They have their own issues because they’re people, they’re not just products of their environment or their parents, though those are obviously a big part of it. It felt really important to me to make them teenagers dealing with a problem that’s political and immediate. I was interested in going to that really hot space and trying to find empathy and truth and specificity with it, because every teenage abortion story is specific and has to do with specific people. It just felt very important to me to make them high schoolers.

We’ve spoken a lot as a production team about how this play is ultimately a story of friendship, and how two people who begin as strangers grow close after sharing an intense experience. Can you speak to that?

I’m really drawn to unlikely friendship stories, and so I started with the character of Amy and I thought, she’s very guarded, she has a lot of friends, but — and I think this is very common with young women who are guarded — she doesn’t want to reach out to her closest friends with an issue, because she doesn’t want that kind of institutional memory of this experience. That’s why I included Reba, as a way to show that Amy has people, and decided not to reach out to them. So that was part of the unlikely friendship story for me: for Amy to be truly vulnerable, she had to be with somebody who didn’t know her at all. I also think female friendship has to be portrayed more. People are really hungry for honest stories — stories without parents, stories about women without boys or men. Taking away these elements shows a female experience that is a huge part of a lot of women’s lives and just isn’t represented very much. Also, in doing that, you don’t get the trope of two super close girlfriends chatting, but two autonomous individuals trying to understand each other and trying to get something done. I was interested in something where the people are quite different, but through a difficult experience find common ground. Tramadol online http://kendallpharmacy.com/tramadol.html

One of the things I love about the play is that you so deftly weave all these various “issues” into the text without it feeling like an “issue play.” How did you decide what to include and what to leave out about what’s going on in the lives of these characters?

I know that I have a minimalist style and I’m very allergic to cliche, so that makes me go to these hot spots where I say, “Okay, I’m gonna do a play that deals with abortion, female friendships, eating disorders, alienation…all of these issues.” That works well for me because I tend to want to tell the least amount of information that I can. Nobody is going to be like, “Oh, an audience is here, so I’m just going to tell you about myself.” So for myself it’s about working with this tension where I have all the information I have to convey, but the challenge of how to do it realistically and without cliche. There’s also the fact that you see a lot of one-issue things, but nobody lives a one-issue life. We have so many intersecting concerns and problems, and so even though it might seem like a lot — tackling somebody with an eating disorder, suicide, somebody who’s going through an abortion — that just really rings true to my life and my experiences. You don’t categorize people like that when they’re real people, so it was a challenge I was interested in representing.

Toward the end of the play, Amy muses a little about what her life might be like as an adult. Can you talk about that moment and the importance of voicing her potential future?

I think that that was a really important moment for me. There was this piece in Elle that actually said it quite beautifully — that the play is about going through an abortion, but also about getting through it and resiliency. So I think that moment is showing that you’re not branded by your experiences, no matter how much that seems to be the case. In this day and age, when there’s so much stigma around things that women go through, I wanted to show that even though Amy is not a perfect person, she’s a resilient person. There are a lot of people in this country who think that that self-abortion is a sin, so there’s a lot going against her, and so the fact that she believes in herself is a really important part of the play.

How did current cultural discussions and depictions of abortion narratives impact the way you approached the play?

It’s easy to be reticent about putting one of these stories out there because there are so few of them. Sometimes I was afraid that this story would become one of the few, and people would take it as a representation of the whole, whereas I just wanted to show that there are so many different kinds of specific abortion stories. So the more media that was coming out, the more excited I was, and the less of a burden I felt about portraying a perfect abortion story — whatever that is. I also did some research and set the play in central Florida, where the closest Planned Parenthood to where I imagine the characters live had been bombed several times in the past ten years. I also wanted to draw attention to the fact that in many states somebody like Ester would be criminalized — it’s criminal behavior to aid somebody in a medical abortion. So all of this was circling around the play, and I absorbed a bit of it, but I also wanted to shut some of it out so that I could make these characters not be representations of the whole, but specific women going through something that I felt was a very true experience.

We had a few women from the Boston Doula Project come speak to our cast, and a big thing we took away from that conversation was that nobody has the same experience with abortion, it is very individual and specific.

I think that’s huge to talk about. I was really interested in trying to take the play out of the pro-life vs. pro-choice conversation, to try and talk about how it is hard, but a lot of things are hard, and there can be resiliency. It isn’t a perfect thing, but it also isn’t necessarily this kind of horrifying, scarring experience. There are just so many difficult experiences that we all go through — someone’s parents getting divorced could be a lot worse than their abortion, or somebody’s friend getting ill could be more difficult. I think it’s really important to talk about how it is a difficult experience, but that it shouldn’t be stigmatized.

Do you consider this a political play?

Yes, I do. There are other representations of abortion that are more like documentary theatre, or about protestors or abortion doctors, and that kind of story is usually labelled as more political. It’s important to me to label it a political play, even though they talk about boys and their hair or whatever. Those things can coexist; a story about female friendship that includes an abortion is just as political as documentary theatre piece on abortion providers.

Studio Sessions︱DRY LAND

Tuesday, September 15 I 6:30 – 8:30pm

Barcelona South End Wine Bar

525 Tremont Street

Part cocktail hour, part exploration of the rehearsal process, Studio Sessions is an opportunity to interact with our productions prior to opening night. Toast Dry Land at Barcelona in the South End, before heading over to the rehearsal room for an inside look at how the show gets pieced together. Complimentary appetizers, cash bar.

Post-show Conversation with Playwright Andrew Hinderaker | COLOSSAL

After the first Sunday matinee of COLOSSAL, director Summer L. Williams and dramaturg Ramona Ostrowski were joined via video by playwright Andrew Hinderaker from Chicago. The discussion ranged from the production process to the problematic culture of football to representations of characters with disabilities on stage, with enthusiastic audience response.

After the first Sunday matinee of COLOSSAL, director Summer L. Williams and dramaturg Ramona Ostrowski were joined via video by playwright Andrew Hinderaker from Chicago. The discussion ranged from the production process to the problematic culture of football to representations of characters with disabilities on stage, with enthusiastic audience response.

Pre-Game Press Conference

Want to hear more from the playwright? Andrew Hinderaker speaks with Dramaturg Ramona Ostrowski about the journey and appeal of “this pressure-cooker of a play.”

Ramona: Let’s have you kick us off, so to speak, by telling me a little bit about where the inspiration for COLOSSAL came from.

Andrew: It came primarily from two different places. There’s somebody in my family who’s a former athlete and has a spinal condition, and watching this person negotiate a new normal, physically, was something that was very much a part of my life. I tried to write about it in a different theatre piece in grad school, and that piece was not terribly successful in executing that story, but it did get me thinking about what it meant to tell a story physically. So that was one piece of the puzzle. Another piece was that one of my closest colleagues who runs the theater company that I’m a part of in Chicago called The Gift is an actor who uses a wheelchair. Our previous collaboration had nothing to do with disability, but working with him really opened my mind more to the intersections of theater and disability.

Also, I was down in grad school at the University of Texas at Austin, and that’s a theatre department that literally sits in the shadow of the football stadium. You know, a 100,000 person stadium that is really the biggest, most popular form of theatre at UT.

You’re not from Texas originally—did writing this play while you were there influence you?

Being there definitely amplified all of the things that were already sort of present for me. The interesting thing about Texas, I think more than perhaps any other state, is that football is so in the bloodstream at every level—Pop Warner to high school to college to the pros. I grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, which is a huge college football town, but the popularity begins in college. Certainly there’s high school football, but it’s not like Texas high school football.

Did you play football growing up?

Did you play football growing up?

I didn’t, other than pick-up tackle games as a child. I don’t have the skill sets and abilities to play. I am pretty flow-less and grace-less. But a lot of people in my life are dancers. That’s really where Texas played a big role in this show, because UT Austin is a department of theatre and dance, and I became pretty close friends with a number of the grad student dancers. Movement really became a central point of exploration while I was down there.

You specify in the script that the role of Mike has to be played by an actor who uses a wheelchair. What made you make that decision, and have you gotten any pushback on it?

I was writing the role with my friend, Mike Thornton, in mind, and never anticipated the play would get a production, much less many! The challenge from my mentor was to write an unproducible play; to do something so big and ambitious that people would be like, “No, we can’t do this.” So initially there wasn’t anything about ability in the script because I thought, “Well, Mike Thornton’s gonna do it.” But once it became clear that we were going to get some more productions after Olney, I realized it was probably something that I should make explicit because Mike couldn’t actually do all these shows. After talking to a lot of folks in the arts and disability community, I realized that a lot of the narratives out there are about overcoming the disability, and then the role is often played by someone who doesn’t have a disability. I didn’t want to be a part of that; I made it explicit in the script because it just felt like a natural thing to do.

No one has said, “Well, oh jeez, then we’re not interested.” I think one thing that speaks to Company One and speaks to all the folks who’ve been great enough to produce this play is, if you’re going to take on a play with a cast this size, with choreography and football players and full contact hits and a drumline, you’re generally not going to be scared off by needing to hire an actor who uses a wheelchair. I think that the piece attracts companies that are drawn to both ambition and to difficult theater. Buy Sildenafil Citrate http://www.sildenafilanswers.com/buy-sildenafil-citrate-100-mg-online/

Company One Theatre is the fourth stop of this National New Play Network rolling world premiere, after Olney Theatre Center outside of DC, Mixed Blood Theatre in Minneapolis, and Dallas Theatre Center. You were directly involved with the previous three productions, right?

AH: Yeah, I was. Very much so with the Olney—pretty much the entire production there—most of the production with Mixed Blood, and at least half of it with Dallas. It’s been great. I’m so fortunate because the evolution of the piece has been so incredibly well-supported, and has really given me a strong sense of what the play wants; what the play is and what it isn’t. It’s been great because I have had the opportunity to work with different directors and different casts in theatres of different sizes. You come away from that experience with revelations for sure.

What are some specific things you’ve learned about the play through the process?

I think one thing that has been proven true from production to production, and is so vitally important, is that the play has a certain precision and relentlessness and violence that isn’t adaptable. There is a certain level of violence in this pressure-cooker of a play where it can’t be allowed to become a little bit sloppy with the movement or the rhythm of the language. If you suck in your breath and tighten absolutely every muscle of your body until everything is unbearable and uncomfortable and tight, that’s the way that the play needs to feel up until that final moment—which is partially why it’s such a short play.

Also, though, the play became about different things in different cities. At the Olney, with an older audience, it became clear that this particular production was about care-taking. In Mixed Blood’s production, there was a little more focus on disability, because that’s something the company is really focused on. And in Texas, the football piece, of course, but also the relationship between two men became what the play was about. There were a number of people who walked out of the play when the two men touched each other. And it was because this particular kind of men, these hyper-masculine football men, were touching each other in a very vulnerable way.

That’s one thing we’ve been talking about in our process—it’s not necessarily the sexuality of the characters that’s dangerous or even interesting about this story, but the intimacy between these two big guys who are so hyper-masculine in a culture where masculinity means closing off emotions and vulnerability.

Exactly. One of the things we’ve always talked about is that it’s absolutely not a coming out story. If Mike had told his father he was in love with his teammate, he would have been fine with it. The interesting thing is that he can’t tell his father because they’ve broken off all ties. Aurogra http://valleyofthesunpharmacy.com/aurogra/

Part of the reason that the play has landed with folks is because we are really drawn to this violent performance of masculinity. We find it attractive, and obviously the play is out to disrupt that, but there is something that’s truly compelling about the play for the same reasons. As a person, and part of a larger society, I’m drawn to this particular brand of masculinity that I find hypnotizing. It’s an incredibly violent game, where these men are asked to really push themselves beyond physical boundaries and to put themselves in positions of extraordinary physical risk. Without question the play is written from the point-of-view of someone who both loves football and finds it grotesque.

Broadening our scope for this last question: what’s exciting to you about the theatre right now? Why do you make plays?

Right now I’m interested in a lot of collaborations that may cut across disciplines—into dance, into sports, into magic, into these forms where people are participating in performance before an audience.

I think that one of the greatest gifts that the theatre can give is the sense of being present. Maybe it’s just me, but I’m so rarely present in my life. In theatre, generally speaking, you’re like, “Sit down, shut up, and don’t go anywhere for the next hour and a half.” If we actually embrace how demanding we’re being, then we might embrace how much we owe our audience. The contract that we’re making is that every moment is going to matter because we’re not allowing you to do something else. We’re not allowing you to look away. So this all has to matter.

That experience that people who love football have when they go to a game that is electric, where they stand on the bleachers and scream? I’m interested in that emotional electricity inside of you. Why can’t the theatre do that? Why can’t it charge us into this animalistic place? At a magic show, people lose their minds. These feats of virtuosic magic are so powerful because they’re actually making us be present; that moment that you weren’t present, you missed it.

I’m not interested in smugness or commentary; I am really drawn to theatre pieces that unabashedly wear their heart on their sleeve—that are unafraid of being emotional. Our contract with the audience is to make every moment matter. That’s the value that I aspire to.

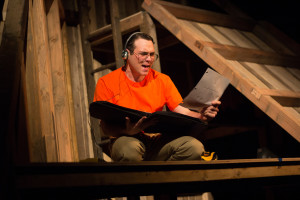

COLOSSAL production photos

90’s Night & Cahllege Mixah!

Our 2nd Cahllege Mixah was a fabulous post-show Karaoke showdown ripe with amazing 90’s hits to fit the time period of EDITH CAN SHOOT THINGS AND HIT THEM. OneRush Member Jose Goddoy hosted the nights festivities.

All had a great time singing along to Whitney, Britney, Fiona Apple, and a bevy of 90’s classics. Big Ups to Joan, who won our audience-favorite prize package, including a stuffed frog (like FERGIE from the show), a copy of George Michael’s album FAITH, and a copy of the script of EDITH signed by the cast and playwright A. Rey Pamatmat!

Special thanks to the staff of the Calderwood Pavilion for hosting us, and to the apprentices from Commonwealth Shakespeare Company for coming out to party!

Production Photos

Check out the EDITH CAN SHOOT THINGS AND HIT THEM production photos!

SHOCKHEADED PETER READ-THROUGH

Check out the beginning of our SHOCKHEADED PETER journey as the C1 staff, cast, crew, musicians, and designers got together potluck style for the first read-through. We have a feeling things are going to get awesomely weird so stick along for the ride as C1 dares to ask what’s underneath the floorboards. CLICK HERE FOR PHOTOS

gala photos

Check out photos from our C1 NEXTasy! Gala

C1 IS FEATURED IN DIGBOSTON’S STAGE SPOTLIGHT

“Aditi Kapil’s DISPLACED HINDU GODS TRILOGY was groundbreaking in more ways than one-play plays shone a spotlight on the contemporary American experience shared by the millions of kids hailing from multicultural backgrounds and addressed issues of intersectionality, gender identity, and dysphoria in an era of post-colonialism.”-DigBoston

CLICK HERE TO READ THE ARTICLE: Year in Review: Stage Spotlight