available for purchase

at this time.

#StaffChat: A Critical Look at THIS IS MODERN ART

Staff Chat posts feature articles and news that the C1 team discusses as part of our weekly all-staff meeting. We’d love to hear your thoughts too — hit us up on Facebook or Twitter!

♦♦♦♦♦

This week’s Staff Chat will focus on the conversation around the play This is Modern Art (Based on True Events), a Steppenwolf for Young Adults production co-written by Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval. We’re looking at two reviews of the play and a few articles that examine the critical reception of the piece:

- — REVIEW: ‘This Is Modern Art’ at Steppenwolf Theatre By Chris Jones

- — Steppenwolf’s deeply misguided ‘This Is Modern Art’ spray paints all the wrong messages By Hedy Weiss

- — Are These Modern Reviews of ‘This Is Modern Art’? By Howard Sherman

- — Playwrights Rip Trib and Sun-Times Theater Critics Over Graffiti Play By Paul Biasco

- — CREATE a movement: the ART of a revolution By Hallie Gordon

Kelly O’Sullivan (from left), J. Salome Martinez Jr., Jerry MacKinnon and Jessie D. Prez in the Steppenwolf Young Adults production of “This Is Modern Art.” (Photo: Michael Courier)

The play, inspired by a real incident, follows a group of Chicago teens who decide to cover the Art Institute of Chicago’s Modern Wing in graffiti art. In their reviews, critics Jones and Weiss briefly touch on the artistic aspects of the play (which they seem to praise), but spend most of their columns taking the show to task for its portrayal of graffiti artists. From Jones:

But here is what “This is Modern Art” barely even mentions: Graffiti comes at a price. It can be invasive, self-important and disrespectful of the property of others — and plenty of struggling folks have had to clean graffiti off something they own or love. Graffiti can be inartful, for goodness sake. More importantly yet, graffiti had the effect of making people feel unsafe in the city. It terrified people. It was only when public officials declared themselves determined to wipe it out that cities finally came back to life, with broad benefits.

You wanna go back to riding public transportation in New York or Chicago in the 1980s? I do not. You do not have to be conservative or somehow not down with youth to think it reprehensible that these issues do not have a place in a show for schools that is quite staggeringly one-sided.

Weiss continues this line of thought in her review, though she takes it even further, stating:

This play is a wildly wrong-headed and potentially damaging work — one that fails to call “vandalism” by its name, and rationalizes and attempts to justify that vandalism in the most irresponsible ways. It also trades in all the destructive, sanctimonious talk about minority teens invariably being shut out of opportunities and earmarked for prison in a way that only reinforces stereotypes and negative destinies. Counterproductive in the extreme, it deepens and solidifies racial and class divisions and a sense of hopelessness among those who need to dwell on possibility.

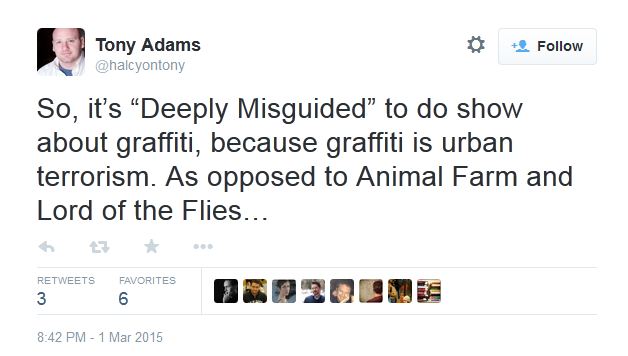

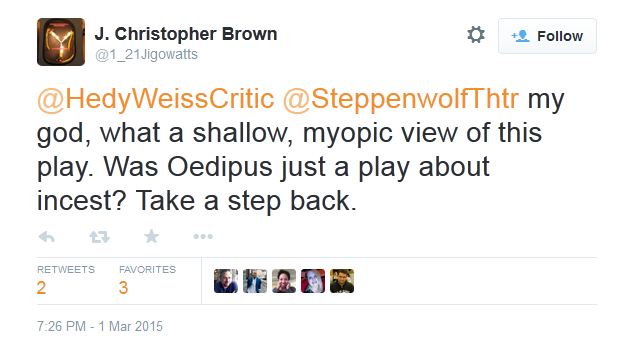

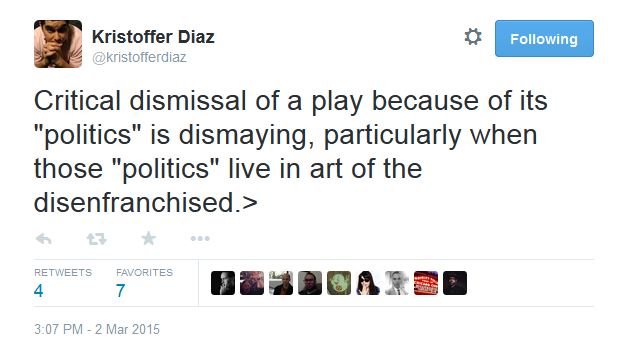

A flurry of conversation followed the publication of these reviews, with many people giving their takes over social media. A lot of theatre artists and administrators, even those who hadn’t yet seen the play, took issue with the way Weiss characterized the teens in the show as “urban terrorists” and questioned the classism and racism present in such a statement:

When asked about their take on the critical response to the play, co-writers Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval didn’t seem shocked by the reviews:

“What I’m not surprised about is old white people, critics for these dying papers, don’t want to celebrate stories about youth culture who have been systematically denied agency,” Coval said. The critics “seem right on message,” he said…The reviews focus more on whether graffiti and tagging is a crime and less on the story and bigger questions it raises, according to both playwrights.

Howard Sherman has a similar view, and took to his blog after observing the social media conversation to give his own well-reasoned critique of the Jones and Weiss columns:

Presumably Chris and Hedy could have noted their displeasure with the play’s perspective while still attending more fully to the details of the play and the production, which they fleetingly praise. Subsequently, as senior critics, they could have easily then written separate essays in which they explored their political and personal reactions to graffiti as vandalism, and question Steppenwolf’s responsibility in presenting the work if they wished, instead of forcing such op-eds into the confines of a standard review.

The critics seem to question the intent behind the piece and the responsibility of the artists involved. Hallie Gordon, the Artistic and Education Director of Steppenwolf for Young Adults, speaks to directly to those points in her HowlRound essay:

Young audiences are smart, discerning, and thoughtful—they consistently exhibit a greater capacity than their adult counterparts to engage with material they find vexing or baffling, troubling or flat-out wrong. It is as teenagers that we forge our convictions—our teen years are a crucible where our personal history seeks to integrate into the wider narrative of the society in which we live… It is an exciting and high-stakes time of life, but it’s also strewn with pitfalls and great potential for trouble. So when my excellent staff and I create our programming, we don’t merely build a show with all that that requires (marketing materials, design decisions, budgeting, etc.), but we also devise and execute an in-depth study guide (providing historical, conceptual, and societal information) of the ideas touched on by the plays we present. Furthermore, we conduct extensive teacher training in our methods and approaches, and we employ a number of outstanding teaching artists who conduct in-class workshops to prepare students for the work we make.

The study guide she mentions can be viewed online – in fact, both critics could have looked to it for insight into the conversations Steppenwolf was having with its audience. Ultimately though, Gordon and the theatre are encouraged by the passionate conversation around the play:

What I find heartening and of greatest interest, here, is that these reviews have sparked a ton of very thoughtful response—in post-show discussions, across social media, in comment threads—on the nature and purposes of art, the intended audience for art, what constitutes a “suitable” venue for it, on questions of access and opportunity, on notions of propriety and boundaries, on aspects of class, race, and education. It is precisely this capacity to debate—even in a heated fashion—that leads me to conclude that the show is achieving its purpose.

The responses to this play raise a lot of questions we’ll be talking about as a group, including:

- — Do you think the critical response to the play would have been different if the show wasn’t especially targeted to teens?

- — Do companies have a responsibility to present both sides of an issue raised in a production? Does that change if the play is geared toward younger audiences?

- — Does this event impact the way we think about our own study guides and how they should be framed?

- — Should critics pen more op-eds, as Howard Sherman suggests, when plays bring out such strong personal responses? Or should reviews allow for a critic’s point of view to be known?

- — Did the critical response to this play draw more attention to the play and its message than a standard review might? If so, does that change your opinion on such reactionary reviews?